The Kindness of Strangers

A lonely event unlocks some deep gratitude

Dear Readers:

I’ve done a few good deeds in my life, I suppose. More often, I’ve been the recipient of kindnesses. What follows is the story of my life during the first week in May five years ago, when I found myself in Buffalo, NY for the first time in my life, in order to be with my father at the end of his.

Below is my account of that week, which I wrote on the first anniversary of my father’s death and sent to my friend Sean Kirst, who writes a wonderful column for the Buffalo News:

Amy Dickinson in Los Angeles, 2019. Courtesy Amy Dickinson

Dear Sean,

Before last spring, I had never set foot in Buffalo. I don’t know why this upstate kid has lived in New York, Washington, London and Chicago, but had never even been to Buffalo. Maybe this lapse is because I spend so much time commuting back and forth between my hometown of Freeville, N.Y., and Chicago to visit my office at the Chicago Tribune and put in my time as a panelist on “Wait, Wait, Don’t Tell Me.”

I think I always assumed that Buffalo was just a Chicago redundancy – two big-shouldered cities stoutly guarding great lakes.

But one night last spring, my father was airlifted from a nursing home in Pennsylvania to Mercy Hospital in Buffalo. Taking this 85-year-old man with a head injury to Buffalo seemed like a fairly random choice at the time, but it was a fateful one.

I guess it’s important to know that if you looked up “Bad Dad” in the dictionary, my father Buck’s name would be there. He tore through life, with no sensor and an indeterminate conscience. His personal GPS was always set to “outahere.”

At the end of this life – after the five marriages, the abandonments, the bad business dealings – I was the only one of his four children who would have anything to do with him. And my involvement with him was pretty minimal.

And so I took myself to Mercy Hospital last May, to be a witness to my father at the end.

One thing about being with someone at the end of life is that the end could come in an hour, a day or a month. I think my original intention was to show up, hand out my phone number to the hospital staff and sneak away.

But Buffalo opened up its big arms and took me in. And so I stayed. I stayed in Buffalo for over a week (my sister joined me at the end), and we experienced such a flow of kindness and generosity, that I wanted to say thank you.

Maybe you could share this with your readers:

Thank you to the staff at the Lafayette Hotel. Each evening when I checked in for yet another night, wearing rumpled clothes and worn-out from my strange and lonely bedside vigil, they found a room for me. And the rooms seemed to mysteriously upgrade as time went on, until finally I was put into a suite that looked like a movie set, which made me so happy that I burst into tears when I opened the door.

Thank you to the couple who treated me to a Buffalo Bisons game one night. All I did was stop them on the sidewalk and ask where the ballpark was (I was standing almost in front of it). And they said, “That’s where we’re going. Come with us!”

They bought the tickets, I bought the beer, the Bisons won, and I forgot about my sadness for one night. Thank you.

Thank you to the staff at Mercy Hospital. Their professionalism and flat-out loving kindness gave one bad dad a good death, and granted one worn-out daughter a measure of peace.

I’m including a series of Tweets I wrote and posted, as I experienced my father’s fading and death. Reading them now, these statements seem like real-time poetry to me.

From @askingamy:

God bless the orderlies and the nurses and the army of people who provide care in our hospitals. (I'm with my dad in the ICU).

Because there are at least 30 people providing various levels of care to my old man. Including Martin, a 6'5" orderly.

God bless the night shift of hospital workers who administer the meds and change the beds and attend to the beeping machines.

God bless the early morning orderlies and the PT lovelies and the social worker half my age who wants to bring me coffee.

Here's to the floor sweeper and the sleepy security guard and the hospice volunteer who will all shepherd you into the good night.

Here's to the hospital weekend staff. They took the tough shifts, missing ball games, picnics, and prom pics — just like their patients.

Here's to the nurse Christine, at the end of her shift, who talks to my dad as she treats him, and then asks what she can do for me.

God bless John, who cleans the room, and Jake, overnight orderly, who says, "Tonight, I'm your guy. Anything you need, you find me."

Here's to the hospitalist, who prescribed a Tim Horton Boston Creme donut, for me. (I filled the prescription. Twice.)

Here's to Shannon, I think she's a PA. She's wearing scrubs and a smile and her pony tail swings as she walks down the hall.

God bless the hospital chaplain, who pops her head in, now and again. My old man was not the praying type, but I might.

God bless the charge nurse, who wordlessly brought in coffee and a tray of cookies, set them by the window, and waved his way out.

Here's to Dr. Jen, who showed me my old man's CT scan and then said, "Cute jacket! Where'd you get it?”

Here's to the family visiting the man in the next room. They look like 'Sons of Anarchy,' but their talk is funny, kind, and tender.

I have no words – only tears – for the hospice worker who helped my family – and my father, have a good death, surrounded by compassion.

RIP to my father. He led a hair-raising life, but was granted a very gentle death. Bless the army of caregivers at Mercy in Buffalo, N.Y.

Now … exactly five years later …

I was handed an opportunity to return to Buffalo, to tape Wait Wait Don’t Tell Me at their historic Shea’s Theater. Below is columnist Sean Kirst’s account of what happened next (I’ve slightly edited it for length). I hope you’ll pay close attention to a point Sean makes — that the kindness I received from that “soft shoed” army of hospital caregivers five years ago anticipated the lengths and strengths they would demonstrate (a thousand times over) during the pandemic.

Sean writes:

“Amy Dickinson is surprised anyone on the office staff at Mercy Hospital of Buffalo followed up at all. The author and columnist left what she calls “the weirdest message” a couple of days ago with hospital administrators, a message that went something like this:

“Hi, I’m an advice columnist on a comedy show that’s also a radio show, and I just wanted to offer some tickets to you for this radio show that’s really a comedy.”

She went on for a while in that vein, and she was a little afraid any staff workers listening might shake their heads, mystified, and simply hit erase.

They did not, much to Dickinson’s gratitude, which is really the whole point. She is a bestselling memoirist whose "Ask Amy" advice column is read around the globe. She will arrive in Buffalo in a few days as a panelist for Thursday’s performance of “Wait Wait ... Don’t Tell Me!,” the well-loved National Public Radio comedy quiz show based on this week's news that has already all but sold out Shea’s Performing Arts Center.

Amy Dickinson, during an episode of "Wait Wait ... Don't Tell Me!" with Adam Felber, not long before the beginning of the pandemic.

The visit has particular meaning to Dickinson, 62, who writes her columns and books from Freeville in central New York, a community hammered by last week’s will-this-winter-ever-end snowstorm. This will be Dickinson's 126th appearance with “Wait Wait,” and she will walk into Shea’s at a moment when the leaves on the maples are finally preparing to come out and the Western New York grass is that specifically vivid shade of early green, all of it underlining how Dickinson feels about the maddening sequence of chilly anticipation she calls "demi-spring," when she says you ache for warm days but do not put away your boots.

“It’s a chance to be in Buffalo at a time when we’re all feeling a little reborn, a chance to reclaim Buffalo in new ways.”

Yet Dickinson’s connection to Buffalo is even closer and more immediate. It intertwines with a growing realization she tries to emphasize both in her daily life and as a columnist: “Compassion, peace, understanding,” said Dickinson, selected years ago by the Chicago Tribune as successor to Ann Landers. “It all starts at home.”

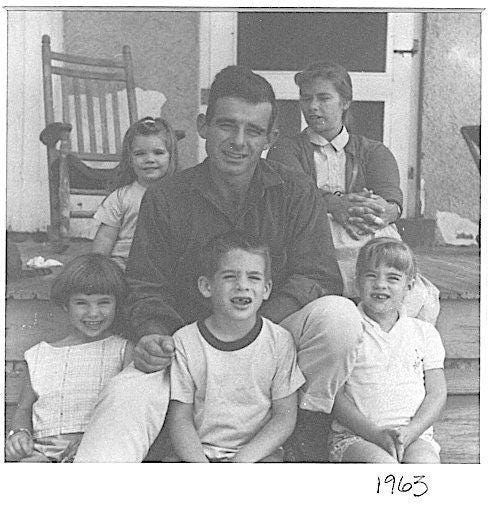

Amy Dickinson, the author and advice columnist, with her family, 1963: Her mother Jane, upper right; Amy, upper left; siblings Rachel, Charlie and Anne, front row, left to right; father Buck, in the center.

Her example becomes the final days of her father, Buck, who died five years ago in Buffalo. “He was the worst father in the world,” Dickinson said, describing Buck as a guy who married five times and walked out on Dickinson’s family when she was 12.

Decades later, he endured catastrophic

injuries in a rollover of his pickup truck.

Buck spent four years in assisted living in

Smethport, Pa., where Dickinson began a

cautious reengagement, until her dad

suffered a massive stroke in 2017 that caused him to be airlifted to Buffalo.

He ended up at Mercy Hospital in Buffalo, and Dickinson came here to be with him and keep vigil. She was alone. No one knew her. It was all part of a revelation she described, day by day, on Twitter: To her deep appreciation, Dickinson was embraced in Buffalo, and the people who lifted her up were not civic big shots conscious of her career or her achievements.

She was comforted, she wrote, by the “orderlies and the nurses and the army of people” involved with intensive care at Mercy, including a warm and supportive guy whom hospital administrators believe was James McDuffie, a beloved environmental services worker who died in 2021 from Covid-19.

Dickinson tweeted about all that support, with quiet awe. She thanked the everyday staff at the Hotel at the Lafayette. She described an encounter on a downtown street with strangers who not only told her about a Buffalo Bisons game at what is now Sahlen Field, but offered a ticket and – as she wrote in a thank-you note to Buffalo – eased her sadness for a night.

She ended her Twitter narrative with this message:

"RIP to my father. He led a hair-raising life, but was granted a very gentle death. Bless the army of caregivers at Mercy in Buffalo, N.Y.”

Now, for the first time since Buck died, she is coming back. She is working with the hospital to provide tickets to at least some of those workers as a show of thanks, while her larger thought about the whole community involves a landscape of thanksgiving that goes something like this:

Dickinson’s column is read by an estimated 20 million people or more. Throughout the pandemic, her mail carried a heavy dose of the fractious and bitter national divide over myriad issues, but she kept her eye on people's more intimate nose-to-nose dealings with one another, and she reaffirmed what to her is a defining commitment.

Amy Dickinson, on the panel of 'Wait Wait ... Don't Tell Me!' Courtesy National Public Radio

Friends she reveres and respects have told her she needs to be nastier as a columnist, that being “mean” works as both a 21st century writing tool and as a digital magnet for readers. Dickinson listens but chooses a different path. She is trying, she said, to go in the opposite direction.

That week five years ago in Buffalo, to her, will always matter in this way:

As a child in Freeville, her father’s abandonment hurt her, and badly. No one would have blamed her – no one, really, even would have been aware – if she declined to be at his side as he died in a city she did not know.

Instead, she chose to be here, and she fell in

love with this community. She said Buck

even left his body to medical science at the University at Buffalo – a decision that he made long ago, by longshot coincidence. The knowledge that came from Dickinson’s choice to show up was a prelude of what became so evident in the pandemic, of how nurses in soft shoes and hospital workers in their scrubs could emerge – at a time and place when it might seem the world has forgotten you – as the most important and supportive human beings in the world.

“My old man was not a great person in many ways, and a terrible father," said Dickinson, who was joined at the end in Buffalo by her sister Rachel. "But I decided at the end to forgive him, not to relitigate everything, and somehow that is sort of like how Buffalo took me in.”

She brings that gratitude to Shea’s this week, as she awaits true spring.”

My follow-up:

I’m happy to report that the Wait Wait taping went really well — the gorgeous performance palace was packed to the rafters.

The sold out crowd included … ten hard-working staffers from Mercy Hospital, who accepted my gratitude in person. I was so happy to see them again.

The hardest thing about accepting the kindness of strangers is that they remain unknown to you. It felt good to close the loop in this way.

{video I shot from the stage…..!}

If you want to listen to the show we recorded in Buffalo (broadcast on NPR stations last weekend):

CLICK HERE

The show is about 50 minutes long.

DEPARTMENTS:

Railey Jane Savage’s JUNK FOOD: DuBois, or Not DuBois

Railey writes:

“I have always depended on the kindness of strangers…”

When I was an artsy preteen in the late 90s, this phrase was the quickest way to demonstrate mastery of an affected southern drawl. But like the floppy disk 'save' icon, or tapping the telephone receiver on your touchscreen phone, the phrase had been divorced from its original context. I ran with an aggressively erudite crew that prided itself on trivial knowledge so we knew the proper response to the kindness-of-strangers call, was to drop to our knees and yell, Steeelllllllaaaaa with as much pathos as we could muster. (It’s no wonder we were popular with adults; less so with our peers.) But—gratefully—none of us could really grasp the relationship between the two phrases.

To be clear: These two iconic utterances come from Tennessee Williams’s raw, provocative, evocative 1947 play, A Streetcar Named Desire. The film version that came out in ’51 is a showcase of powerful performances by Marlon Brando, Karl Malden, Kim Hunter, and Vivien Leigh. Leigh plays “kindness of strangers” Blanche DuBois, and Brando is her “Steeellllaaaa” brother-in-law, Stan Kowalski. Brando’s machismo ripples through the screen, and Leigh’s performance is distressingly accurate as she toes the line between genteel, and broken.

Blanche DuBois is absolutely broken. She is tired, aging, needy, and practically unable to care for herself. Then she gets assaulted by her brother-in-law. And in response—retaliation—she is institutionalized. When a doctor comes to collect Blanche she has separated with reality and misidentifies him as her knight in shining armor, then utters her final line, “Whoever you are – I have always depended on the kindness of strangers.” It is a profoundly sad, deeply troubling exit line that demonstrates how the weft of a narrative can get warped (even by its protagonists) in a distressingly unironic way.

After my brother died I went into a kind of tailspin. Then more horrible things happened, and I did not do a good job of coping. So, what outwardly appeared to be a good-time-party-girl, was really just me flailing in public. One night I drank myself silly in my go-to bar and fell, and then just sat on my knees on the dirty floor and started to cry. I was a hot mess.

A couple crouched next to me to see if I was alright… I wasn’t injured, but I wasn’t alright. But they met me where I was at. They bundled me into their car and drove me down the hill to walk me to my apartment door. They probably saved me from whatever horrible things await distraught women at night. I remember thanking them through my tears and insistently brandishing my wallet to pay them for their trouble. I remember telling them how sorry I was, and that I hated needing help. And I remember the woman replying, “Sometimes we all need help. Even strangers.” They didn’t take my money and I never got their names.

I’ve spent the past ten years working intently to feel less broken. The mouthy theatre girl, and the tragic barfly, and the introspective survivor are all versions of myself that still exist, but are no longer at odds—these Raileys are not strangers. But they still benefit from kindness. So now instead of shouting “Stella” when I hear the DuBois dictum, “I’ve always depended on the kindness of strangers,” I check myself, and my gratitude. Then I reply, “Me, too.”

[Railey Jane Savage is the author of A Century of Swindles. Find more of her essays, books, art, and cats at raileyjane.com.]

Laura Likes: (where my friend Laura recommends great stuff)

… if you want to spread a little kindness this weekend, here is a traditionally Southern way to celebrate:

Laura writes:

“The Kentucky Derby is traditionally run on the first Saturday in May. There have only been two exceptions since the inaugural race in 1875. The first was in 1945, when there was a ban on horseracing from January to May because of World War II restrictions on manpower and travel. After V-E Day...which as it happened was three days after the day the race was supposed to have been run...everyone scrambled and they held the race in June. They also postponed it in 2020, because of the pandemic, and it was run in September.

It's an event loaded with tradition and lots of food...and of course, the hats...and as a native Louisvillian and actual Kentucky Colonel, I thought I'd share my thoughts on the official Derby drink, the mint julep.

It's one of those drinks everyone thinks they know how to make, and I looked online and found a lot of how-to guides. I'm of the opinion that you should make it the way you like, but this is my approach.

First of all, use a traditional metal cup. It's supposed to be cold, and julep cups are designed to be, and stay, cold. Hold it by the foot of the cup so you don't warm it up with your hands too much. You can stick it in the freezer for a bit.

Second, use fresh mint. Don't pulverize it. It's not pesto. Press it with a muddler lightly to release the essential oil.

Third, you need sweetener. It's supposed to be a sippin' drink, and it's supposed to be pleasant. It's not a contest. You walk around with it, pretend you are a person of leisure. You can muddle the mint with sugar, or you can use sugar syrup. If you use sugar, use a light hand with the muddler because the granules of the sugar will help rough up the mint. Mint gets bitter if you get really aggressive at crushing it.

For this drink, I actually prefer to sweeten it with a rich syrup (2:1 sugar to water), instead of simple syrup (1:1 sugar to water), because it tastes good, gives a bit of a thickener effect, and frankly dissolves a lot better than just using granulated sugar. Just a personal preference. it's totally up to you.

Fourth, use cracked ice. I prefer mine cracked a little larger than most people. I like the drink to gradually become watered down, not instantly watered down when you pour bourbon over shaved or powdery ice.

Ice in cup, mint + syrup + bourbon in the cup over the top, pile up some more ice on top. Ta-da.

Fifth, use a big garnish of more mint, why not. It looks nice.

Enjoy responsibly. (Non-alcoholic versions are nice too, just basically make a strong, sweet mint tea and use that instead of bourbon.)

My grandfather used to say "there's nothing quite like the spring in your step when you've got a two-dollar win ticket in your pocket." Happy Derby Day and I hope you have a great time, whether you're at Churchill Downs, at a big fancy party, or just hanging out in your yard.

Riders up!”

Dear Readers: I hope you receive slices of kindness wherever you go.

As always, if you have read and like this newsletter, shoot us a “heart” below. We appreciate it so much. And definitely share your own stories in the comments section.

Love,

Amy

My heart is both broken and full after reading this essay. Thank you for always going to the "good side" of life.

Very very touching! Thank you, once again, for providing a continuing perspective on kindness!