Dear Readers: Merry Christmas! In honor of the holiday (which I love to distraction), I’m sharing what I’ve come to think of as my annual re-telling of a story I published as a chapter about faith — in my first book, “The Mighty Queens of Freeville.”

This is dedicated to my dear daughter Emily. My best Christmases are those where she is nearby.

[Luminaries light the way in…]

When I last saw him, Peanut Jesus was lying swaddled in a teeny tiny piece of paper towel, resting sweetly in his cardboard manger. I turned my back for a minute in order to stop a covey of boys from putting together a table-top football game pitting the Wise Men against Joseph and Mary.

I admit that what happened next is something I probably should have anticipated. In my five years of teaching Sunday School to 8 and 9 year olds at our church in Washington, I had already faced an ark full of pre-adolescent shenanigans, many having to do with our craft projects and the holy family. I trained myself in the art of the “teachable moment,” even at one point uttering the phrase, “Yes, Steuart, that’s right. The Virgin Mary does have nipples. Class? Why does the Virgin Mary have nipples? Anyone? Because she was a woman. And she was a mom, too. Does anyone know whose mom she was? No?”

After my little Aristotelian monologue, delivered to the mostly smirking and freshly scrubbed faces of my prosperous little charges, I pretty much wanted to run screaming onto the street, hail a cab and go to the nearest bar, until I realized that it was 10:15 on a Sunday morning and if I was lucky enough to find anything open, it would most likely be crowded with Sunday School rejects such as myself – and the last thing I wanted at such a moment was to be in proximity to people who shared my predicament and had been driven to drink by a room full of second graders.

My class of around 15 kids, which convened after the 9am service, trooped over to the education building while their parents cruised out to have coffee or a quick brunch at a café. Our weekly 90-minute sessions were a blur of snacks, stories, simple prayers and crafts. I liked sending the kids home with something we had made together and got pretty good at thinking up new ways to illustrate the Bible stories we were reading in class. Old Testament-wise, my class and I could knock out individual milk-carton chariots driven by clothespin Philistines in about half an hour. Our Popsicle stick Ark of the Covenant took two sessions, but only because the glue needed to dry.

My crafty crowning glory, however, was the cereal box crèche.

This elaborate home made nativity scene featured a stable made of a cut up cereal box populated with cotton ball sheep, cardboard camels, and the holy family, which we made from toilet paper rolls. The star of the cereal box crèche was Baby Jesus – a peanut still in its shell, swaddled in a tiny piece of paper towel and laid in a cardboard manger.

[My cereal box creche]

My class of kids happily participated in the manufacturing of our crèches, cutting, gluing, and excitedly talking about Christmas. We assembled our individual Nativity scenes and reviewed the miraculous story of the birth of the baby Jesus. Then they drifted into their favorite classroom activity, which was to goof around.

While my back was turned, I heard the familiar crack of a peanut shell. The faintest whiff of peanut essence escaped into the atmosphere, like a tiny puff of organic life being released into the stale air of our basement classroom. By the time I turned around, Peanut Jesus’ manger was empty. I knelt down, face to face with Wyatt West. He was wearing his usual Sunday School outfit – a tiny pair of chinos and a Brooks Brothers navy blue blazer over a light blue oxford shirt. He had little clip-on necktie. Like many of the boys in my class, Wyatt always looked to me like a miniature Congressman on a constituent visit. He was holding two empty peanut shell halves, looked blankly at me and said, “Wha..?” A small fleck of peanut skin dangled at the corner of his mouth.

"Did you just eat Peanut Jesus?“ I asked him.

"That was Jesus?” he said. “I thought that was Joseph.”

I decided to ignore the implication that it was somehow all right to eat Peanut Joseph and cut right to the chase.

“No. Joseph is the dad. Class? Who is Joseph?”

I picked up Joseph. His body was made from a toilet paper roll, which we had glued fabric onto and accented with pieces of yarn. Joseph’s eyes were pinto beans and his mouth a piece of macaroni. We used little cardboard flaps to make his flipper-like hands and feet.

“This, my friends, is Joseph,” I said. I held Joseph aloft. He looked exactly like a toilet roll in drag. Ru Paul, by way of Charmin.

Later, on our way home in the car, I reviewed the events of the morning and asked Emily, as I often did, where I had gone wrong. She was a diligent and cooperative 5th grader who didn’t have me for a teacher and so could rattle off all the books of the Old and New Testament in 36 seconds. I was hoping she would have the perspective I lacked on my class of primary schoolers. “Mom, second grade kids are jerks. Especially second grade boys. They’re total spazzes, too. And they have potty mouths. Have you listened to the way they talk? Honestly, sometimes I don’t know why you bother.”

“Thanks,” I said. “That was very helpful.

While I was aware that other Sunday School classes at our church’s efficiently run education program seemed to impart actual information, my own class of kids retained startlingly little. Sometimes I wondered why they kept coming, week after week, until I realized that most second graders don’t exactly have control over their own schedules. Like Emily, these kids came to church because that’s what they did on Sundays. It was like soccer practice, ballet or Little League. They showed up because their parents drove them there.

The following week, I took my concerns to the rector of our church, Rev. Kenworthy. "The kids – I don’t know. I don’t know if they are getting much out of what I’m doing.”

“You’re there. You’re there every week and this is your ministry,” he said. Like a wise person who answers a question with a question, he dodged my concerns by praising my intentions.

But ministry?

I didn’t think so.

I started teaching Sunday School when Emily was in Kindergarten, soon after we started attending Christ Episcopal Church in the fanciest part of swanky Georgetown. I wanted a place for the two of us to go on Sunday mornings, which for me have always felt like a yawning, mournful void – a time when I feel overly homesick and sorry for myself; a time that I only know how to fill with church. The church I chose was fairly high-church Episcopalian; its pretty gothic interior burnished with the scent of 100 years worth of incense. I had attended this same church occasionally when I was a student at Georgetown, whenever I needed a Protestant refuge from the Catholicism of my college. Famously, some scenes from “The Exorcist” were shot in the church’s small side garden. Some mornings, while lingering in the garden during the coffee hour, I pictured Jason Miller, brooding and intense, keeping Satan at bay and surrounded by a film crew.

I grew up in a churchy, if not overtly religious home, and attending church is one childhood habit I’ve never seen fit to break. The only years when I didn’t attend services regularly were when my husband and I lived in New York City together during the mid-1980s. Then, our Sundays were fully committed to the official New York religious devotions of reading the Sunday Times and buying things. Once we moved to London and my husband’s job removed him from the Sunday equation, I started occasionally attending church again, always on my own – popping in to a small Anglican church on the pretty square across from our apartment.

Emily’s first Christmas Eve was spent in a snuggly strapped to me as I stood in the back of the sanctuary of the small church on our London square, sobbing quietly with loneliness (my husband was away) as I followed the candlelight service and wondered what my family was doing half a world away in Freeville. She was two months old and her family hadn’t yet met her.

I wanted for Emily to know God. I thought I could make the introduction and perhaps stick around for awhile to see if these two strangers struck up a cordial conversation. I was like an ambitious hostess at a cocktail party – I didn’t want to force a relationship but once the two started to talk, I would quietly disappear and hope it took.

Later in January during Emily’s infancy we flew to the States – all three of us – in order to baptize her at the Freeville United Methodist Church. Like most things we did together during our brief time as a family, I was the tour guide and my husband the tourist, detached from the experience itself but ready with a camera to photograph it. He was a natural-born chronicler, used to looking at life through a lens and of course because he was so often taking the picture, he was frequently missing from it. Our photo albums were mainly records of a mother and a daughter having experiences together, prefiguring our life to come.

My hometown church, next to the elementary school on Main Street, has always been one of my favorite places. Like everything else in Freeville, our church had become an exaggerated version of itself with the passage of time. In January, blanketed with snow, it looked like a New England white steepled church such as you might see in a painting by Grandma Moses, but, like much else in the village (including its inhabitants) up close it was obviously a little the worse for wear. It was faced with aluminum siding in the 1960s and moisture in the joints between the metal clapboards forced little rust stains (they looked like rusty tears) down its front. A marquee with press-on letters announced that week’s message – “Come Home to Jesus.”

Inside, the small narthex gave way to the warmth of the sanctuary, which is wrapped in highly varnished maple wainscoting. Jesus stares benignly out at the congregation from his assigned place – high on the wall, next to the altar. Jesus’ portrait, reproduced in the 1950s, has a muted, photo finish quality. It’s a head and shoulders shot of Jesus, which in its pose and composition looks exactly like a high school yearbook picture. Jesus has a surfer smile, Tiffany blue eyes, a trim beard and shoulder length chestnut brown hair. He looks smart and nice. He’s definitely the valedictorian of his class.

On Sundays when I was a kid, swinging my legs against the pew and hallucinating with boredom during the service, I’d stare at Jesus’ yearbook picture and pray for him to deliver me from evil – and the agonies of the sermon. Whether due to divine intervention or good luck, I was spared both.

The United Methodist Church is not only a house of worship, but it is also the place where things happen in Freeville. The church is like a town hall, performance venue, and all-you-can eat casserole buffet rolled into one. The congregation more or less runs itself according to an ambitious calendar made up not necessarily of holy days but of pot luck suppers, coffee hours, barbeques, festivals, rummage sales, skits, cantatas and hymn sings.

Many of our gatherings revolve around the eating of casseroles, pies, poultry and any vegetable served in white sauce or Campbell’s condensed cream of mushroom soup with shredded cheddar cheese and crumbled saltines on top. The church kitchen is staffed by a group of volunteer women who prepare and serve the meals by which we feed our faith. They engage in a cheddar cheese ministry of the highest order.

Among the kitchen ladies are my three aunts, Lena, Millie and Jean. They wear aprons over their good clothes; their faces blurred by the steam rising from the massive pots they use to prepare their specialties – mashed potatoes, mashed squash, candied ham, or the church’s legendary chicken barbque.

On summertime Saturdays for the last 50 years a small committee of men have gathered at dawn at the barbque pit across Main Street from the church. They lay out the coals and light them. By 8am, the coals are white with heat and they line up dozens of chicken halves on large wire racks, sopping them with a marinade-soaked brush. Within an hour the chickens start to cook and the vinegar scent of the marinade drifts through town.

When I was a kid I’d climb on my bike at the first whiff of barbeque and show up at the pit, hanging around and listening to the men talk about chickens, their jobs, their wives and kids, and what needed to be done to the old building to get it through another winter. I liked listening to these men talk. I never saw my own father at church – or the pit. These men were his age, but they weren’t like him. They were gentle, witty and tolerant, where my father was profane, sharp-edged, unpredictable and bigoted. I was drawn to their devotion, expressed as it was through the delights of slow cooking poultry. The money raised would go back into the church, used to finance a new roof or for Sunday School materials, or put into a fund to send kids to Bible camp.

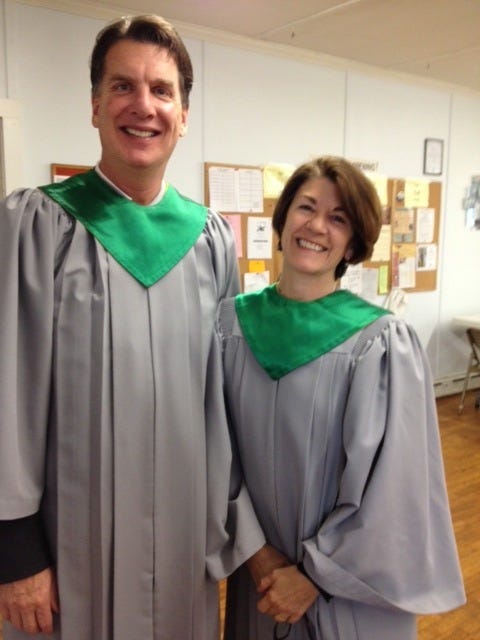

Church has also always been where my musical family sings together. My mother and aunts, cousins, sisters and I are all natural born harmonizers with perfect pitch who might have made something of ourselves, musically, except for the fact that along with all of our talent and natural showoffiness also came a stifling lack of ambition.

My sisters and I sang together in the youth choir and a revolving chorus of my mother, aunts and cousins sang in the adult choir. About twice a year – usually at Christmas and Easter – the church calendar brought all of us together in a case of harmonic convergence that sent shivers up my spine. Singing one of the grand old songs from the Methodist hymnal like, “There is a Balm in Gilead,” I could hear my mother, aunts, cousins and sisters’ voices blending in such a perfect braid of sound that it took me outside of myself.

It was the sound of my family’s gene pool choir that first brought me into the mysterious community of faith and casseroles and made a believer out of me. Surely God had put my family together in such a place, dressed us in red flammable polyester robes in order to sing “The Angel Rolled the Stone Away” with one beautifully blended and pitched celestial Broadway voice underneath Jesus’ yearbook picture for a reason. He. She. Exists.

For her Freeville baptism, I dressed Emily – just three months old – in a long white Victorian christening gown that Rachel had given us and our little family stood before my ample extended family (my mother, sisters, aunts and cousins in their usual pews) and the rest of the small congregation while the minister brought her into the fold with a dab of holy water, a smear of oil, and a lit candle passed over her head. The congregation was asked to renounce the devil and then promised to be a witness to my child’s spiritual life.

I looked out at the congregation from our place at the baptismal font and took solace in the fact that every last one of the people in the room had also faithfully borne witness to me. For better and worse, they abide.

After the baptism, we posed in the snow in front of the church together. The painted plywood nativity scene leftover from Christmas was still up and we briefly placed our baby on the straw of the empty manger and stepped back to enjoy the scene. I remember looking down at her and hoping that she would be blessed with moments of grace. I wondered if she would somehow bear the spiritual imprint of the community of faith and casseroles into which she had arrived.

As Emily grew I wanted her to understand and participate in the age-old rituals that had always given me so much comfort. Our lives, bifurcated as they were between city and country, were split spiritually, too. In Washington we read from the poetic Book of Common Prayer and formally celebrated various feast days with special services and communion. The Episcopal service was beautiful, cerebral, and unchanging. The congregation was top heavy with Washington luminaries – undersecretaries of state, treasury department officials, and other notables – including occasionally George and Barbara Bush and their secret service detail

In Freeville, the service was hung onto the foundation of the Methodist lectionary, but it seemed to vary dramatically from week to week, based on what was happening around town.

The most popular portion of the Methodist service was “Joys and Concerns,” when any member of the congregation could stand up, speak his or her mind, and ask for prayers. Joys and Concerns would often gallop out of control, taking the worship service – and us – with it. The minister would dash up and down the aisle of the church like Phil Donohue, passing a microphone to congregants so they could have their say: “My mom’s back went out again so now she’s going to go to Syracuse for surgery.”

“Donny’s boss says they’re doing another round of layoffs. We don’t know what’s going to happen yet.”

“We’re leaving the day after Christmas to go down to Florida to see our folks. We’d like travel prayers.”

“Dad’s pain is getting worse; they think it might be his kidneys this time.”

“Oh, I don’t need the microphone. I’ll just yell. What I wanted to say is that the JV team is doing really well this year but the Varsity lost again on Friday. The defense just can’t get it together.”

“I’m really happy to see Amy and Emily here again. I hardly recognized Emily, she’s getting so tall! I hope we’ll be seeing them in the choir while they’re here.”

Joys and Concerns is like the world’s smallest radio station broadcasting the news of a very particular patch. Much of the headlines seem related to gall bladders, surgical procedures, and waiting on test results. Some of our news is sad and some is truly tragic, but the congregation also shares their triumphs – the new jobs, new grandchildren, or this year’s bumper crop of zucchini. Joys and Concerns is where the community announces what is important. Then they ask for prayers and receive them. It is the most honest, fair and just exchange I have ever witnessed.

Still smarting from my Peanut Jesus debacle, Emily and I packed the car and drove north, where we rejoined the Freeville United Methodist Church broadcast. We left our big city church, with its staff of well-trained clergy, its historical significance, large endowment, massive charity efforts and Exorcist movie tie in and came home to a place that doesn’t do communion very well, but excels at community.

On Christmas Eve, Emily worked with the hardworking luminary committee, setting up the luminaries that run the entire length of Main Street. These were made of chopped-off plastic gallon milk jugs, weighted with sand and with a candle placed inside. In the daylight, these jugs, placed three feet apart and nestled into snow banks, looked like the grubby remnants of recycle day. But in the dark, glowing from their candles, they lit a runway leading directly into the United Methodist Church. Our Christmas Eve service, crowded with families and fussy babies, ended, as it always did, with the lights dimmed as we sang “Silent Night” by candlelight. Everything got quiet.

We exited the church in silence, walking out onto Main Street. The luminaries were still flickering. Emily whispered, “Mom, check that out…”

Across the street, positioned under the pavilion of the barbeque pit, several members of the congregation had formed a living nativity scene. The three Wise Men wore bathrobes knotted at the waist and dish towels on their heads. Mary’s costume was a lovely royal blue; her hair was tied in a head scarf. She was gazing, lovingly, at a plastic doll positioned in the manger. Two painted plywood sheep grazed in the foreground.

Until that moment I had never quite understood the purpose of a living Nativity, where the object isn’t to act out the Christmas story but to portray a fleshed-out but stationary tableau version of it. Looking at my neighbors dressed in their robes and dishtowel head dresses I saw a life sized version of my cereal box crèche.

“Mom, look – it’s Mr. and Mrs. Eggleston. What are they doing?” she whispered to me. I whispered in reply that they were going to stand there until Midnight and that they were awaiting a Christmas miracle, just like all believers do on that night.

“Do you believe in miracles?” I asked Emily.

“Well, I did pray for something,” she said.

I pictured her modest wish list for Santa Claus; it included ice skates, a sled, ski poles, and an elaborate American Girl doll play set, which I learned was out of stock when I had tried to order it – which was a good thing because I couldn’t afford it anyway.

“What did you pray for, honey?” I asked her. Please let it be a Monopoly game, knitting needles and yarn – and the Polly Pocket veterinary clinic, which I had purchased instead.

“I prayed for snow.”

“Oh. Well, that’s a nice thing to want on Christmas.” I reflexively looked toward the sky and watched the steam from my breath float upward in a column of condensation. A cloud was passing in front of the moon, but otherwise the night was star struck and clear.

I looked at Sue and Keith Eggleston, now dressed up as Mary and Joseph. I had known them both since high school. They were standing as stock still as the plywood sheep, trying to create a flesh and blood telling of an ancient story. A few cars driving down Main Street carrying last minute shoppers home from Wal Mart slowed to a crawl, their headlights sweeping across the scene.

I thought about what Rev. Kenworthy had said about my ministry. Some people preach from the pulpit, moving people toward belief or action. Others, like our Freeville neighbors, minister by sharing their joys and concerns, by cooking and selling chickens or by dressing in their bathrobes and standing in the cold while they demonstrate their faith to the community. All of us had something in common – the desire to show up, to be a witness to others, and to patiently await a miracle. I had introduced Emily to God. Eventually, she would see that when prayers go unanswered, you learn to change your prayers. She would learn that faith, like the seasons, comes and goes. I knew that I would return to Washington, go back into my classroom of little smart alecs, and try again.

Emily and I stood with our family in a small arc outside the bar b que pit, quietly watching the Nativity scene as the first flakes of snow started to drift down through the inky blackness of Christmas Eve.

Was this a miracle or a coincidence? I decided it didn’t matter. If I’d learned nothing else from my small town upbringing, it was that I would have to take my joys where I found them.

And so I did.

Dear Readers,

Merry Christmas! I hope you have a simply and joyful celebration.

Love,

Amy

Thank you Amy, what a beautiful story!

Wishing you and your dear ones a very Merry Christmas! ❤️🎄

my Sunday School teacher was quite adamant: Mary did NOT have nipples!