Literacy always starts with a story:

Giving books for holiday gifts is the best way to build a culture of literacy

Dear Readers: For the past fourteen years, I have devoted one December column entirely to the idea of giving books to children on Christmas morning (or whatever wintertime holiday you celebrate).

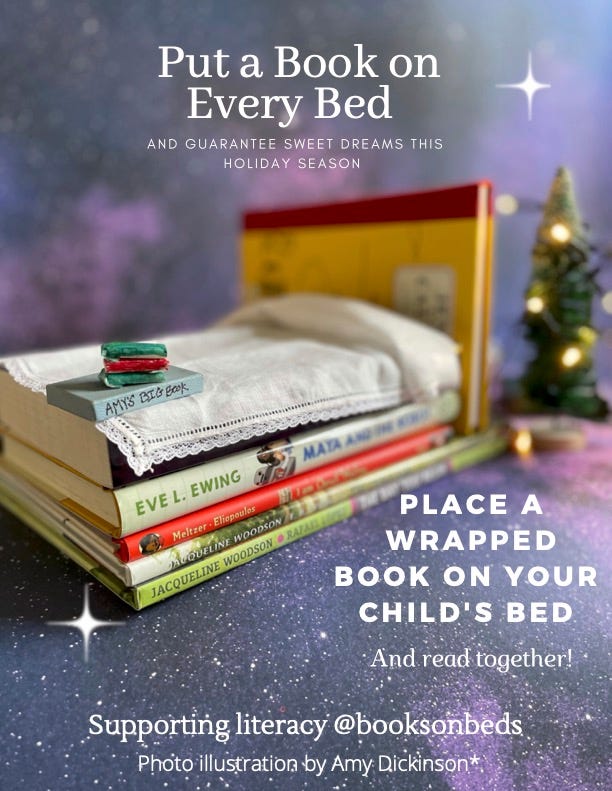

I was first inspired by a sweet story I read about historian David McCullough’s childhood, where he and his three brothers would wake up on Christmas morning to a wrapped book, left by Santa on the foot of their beds.

I communicated with Mr. McCullough, and from his home in Massachusetts he confirmed the story and generously gave me permission to use his childhood tradition to encourage families to start their holiday by unwrapping a book – and reading together.

That’s the origin story of “A Book on Every Bed,” and in the years I’ve published this appeal (to give books to children, and to start your holiday by reading together), it has grown into a literacy campaign. Schools, libraries, book stores, churches and community centers have picked up this idea and are helping families to bring books into their households during the holiday season.

My own literacy story starts with my mother, Jane, who, despite some rough circumstances during my childhood showed her four children that books and literature would always illuminate the way toward better things. She was the person who said to me, “When you have a book, you’re never alone.”

One of my favorite memories of my mother involved catching her reading Anna Karenina while seated in the crowded bleachers during a noisy high school basketball game.

(Final score: Tolstoy 1, basketball 0).

I was allowed to get lost in the stacks of our tiny local library, eventually discovering the books that would change my life: The “Childhood of Famous Americans” series (currently published by Simon and Schuster). I plowed through these biographies with the hunger of a young person desperate to read about “real” people who overcame their own childhood challenges and went on to lead extraordinary lives.

[I loved reading about women athletes. My favorites from this series featured girls who overcame great odds and went on to do great and good things — including the story of legendary Olympic runner Wilma Rudolph. I was obsessed with her story.]

Over the years when approaching some of my own literary heroes, they have spontaneously chosen to tell a story about the special book in childhood that unlocked literature’s secrets for them. Like me, they were lucky enough to have at least one adult in their lives who gave them the gift of literacy. Below are edited versions of some of these stories:

Jacqueline Woodson wrote: “My mother wanted us to read constantly but didn’t have the money to buy us ‘piles of books.’

“To have a brand-new book to open at night — it’s crisp unbroken binding, the scent of its pages, the soft rush of air and excitement that comes with turning them — this is my dream for every child.

“A pile of books begins with one. And like a child, it grows.”

LeVar Burton: “Literacy is the birthright of every human being, even in this digital age. I simply want our children to read!”

Dr. Carla Hayden: “Literacy is the ticket to learning, opportunity and empowerment. It’s important that children see themselves in the books they read. Marguerite de Angeli’s ‘Bright April’ allowed me to see myself in a book – a young girl who was a brownie with pigtails – and it inspired me that anything was possible.”

Brad Meltzer: “Growing up, my family didn’t have a ton of money. But my grandmother had one of the most powerful objects in existence: a library card. I still remember her taking me to the public library in Brooklyn, New York.

“It was a day that made my world bigger and immeasurably better. And the best part were the new friends my librarian introduced me to, like Judy Blume and Agatha Christie. “Superfudge” was the first book I ever coveted. But it was Blume’s “Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret” that rocked my socks. No one understood why I was reading it. But I was a boy trying to figure out how girls worked.

“From there, Judy Blume taught me one of the greatest lessons in life — that you must love yourself for who you are.”

This year I turned to author, screenwriter and poet Sherman Alexie. Sherman is author of one of my favorite memoirs (which is widely taught in high schools and much loved by many): “The Absolutely True Story of a Part Time Indian.” He also wrote the screenplay for the wonderful movie, “Smoke Signals” (based on his own short story collection).

[Sherman Alexie also has a really great and creatively versatile newsletter on Substack (linked here). Please subscribe!]

Sherman generously shared his own literacy story, and, like all good stories, his contains twists, turns, and revelations. He writes:

“I grew up poor on the Spokane Indian reservation so there wasn't always money for new books. But there was Dutch's Pawn shop in Spokane where they sold shopping bags of used books for a dollar or two.

“There would be ten or twelve books in those bags. A very random selection. Lots of non-fiction about WW2. Romance, spy, and western novels. Self-help. Auto repair manuals. I read all of them. And my father read all of them, too. With limited carpentry skills, he built a bookshelf of discarded wood so we'd have a place to keep our shared library.

“Then, one day, I opened a bag and pulled out The Old Man and the Sea, the famous novella by Ernest Hemingway. I'd never heard of the book or author. I started reading and immediately knew it was something different. It was like I was being told a story by a tribal elder. It was magical. Then my father read the book. Afterward, he said, "We need to read more books by him." And together my father and I read all of Hemingway. I learned that there are books that will utterly change your view of the world. And it all began with a paper bag of used books in a pawn shop.”

Looking for great books to give as gifts this year? Here are Sherman Alexie’s picks (with links):

Space: 10 Things You Should Know by Dr. Becky Smethhurst. A lovely short explanation of major interstellar objects and ideas. It reads like poetry.

The White Bone, by Barbara Gowdy. This is a a novel about endangered African elephants on an epic journey to safety, except this story is told from the first-person perspective of the elephants. Yes, the elephants tell their own story. Stunning.

The Chocolate War, by Robert Cormier. A novel about economic and cultural elitism set in a private high school. Our hero rebels against unjust norms and endures physical and psychological abuse in doing so. One of very best YA novels ever written.

Last Christmas, working with the Children’s Reading Connection (childrensreadingconnection.org), a national literacy campaign based in Ithaca, N.Y., I received the thrill of my own career as a reader and writer by giving each child, teacher and staff member of the rural primary school of my childhood books of their own to take home.

Watching these children clutch their new books tightly was a joy and a reminder that literacy really starts with a human connection.

I hope that readers will be similarly inspired to spread the joyful experience of starting their special holiday with a great story.

CONTRIBUTORS:

[For this special edition, I’ve asked my regular contributors to write about a favorite book (or series) from childhood.]

JUNK FOOD: Voyage of the Daunted Reader, by RJ Savage

RJ writes:

“Much to my mother’s chagrin, I wasn’t a big reader as a child; TV and movies were my bread and butter. I could spend hours in front of the living room set clicking through channels 05 – 60 in search of something interesting. In the same way one might stalk the stacks in the library, I would check out Cartoon Network before hopping over to TCM, then TNT, then Nickelodeon, then PBS. Like judging a book by its cover, I gave whatever was on about four seconds to appeal to my nascent sense of [good?] taste.

One day after school—second grade, maybe—while clicking through all the channels, a show immediately hooked me with the image of an enormous mouse in pantaloons with a feather in his cap, scurrying along the deck of a dragon-headed boat. (It was the early 90s, so live action, mind you.) This ticked a lot of my boxes, as it turns out: fantasy, nautical stuff, “history,” British accents. The episode was half over but I watched through to the credits and the flowery script that rose slowly up the screen read, “The Chronicles of Narnia: Voyage of the Dawn Treader.”

What? I knew some of those words, but when I asked what the others meant I was met with the household’s rote response: Look it up. The dictionary helped with “Chronicles,” “Voyage,” and “Treader,” but what the heck was “Narnia”?

The question took me to the reference desk on our next visit to the big library. I toddled behind the smiling librarian as she led me to the “L” shelf to pluck a battered volume with four children in a spooky forest on the cover. “Here you go,” she said, handing me The Lion, The Witch, and the Wardrobe.

A book? Fine, I’ll try it.

I slowly read my way through the entire series, relishing the imagery and the courtly politics. I would shut my eyes and picture the White Witch, and Aslan, and Prince Caspian, and Bree the talking horse. And whatever Turkish Delight was. Then, I’d rush to the library to check out tapes of the BBC adaptation to watch over and over.

I still wasn’t much of a reader, but these books were my gateway to thinking about the many ways one can consume writing: TV led me to books, which led me back to TV. And much later, back to books.

I still have the set of Narnia paperbacks I ordered from the Scholastic Book Fair in third grade. I also have most of the library’s tapes of the BBC series from when it sold off its video collection. The books and the tapes stand together on my shelf—kin, not competition—as a reminder that it’s not important how a kid kinds her way to the page, but that she comes to appreciate the written word in all its varied forms.”

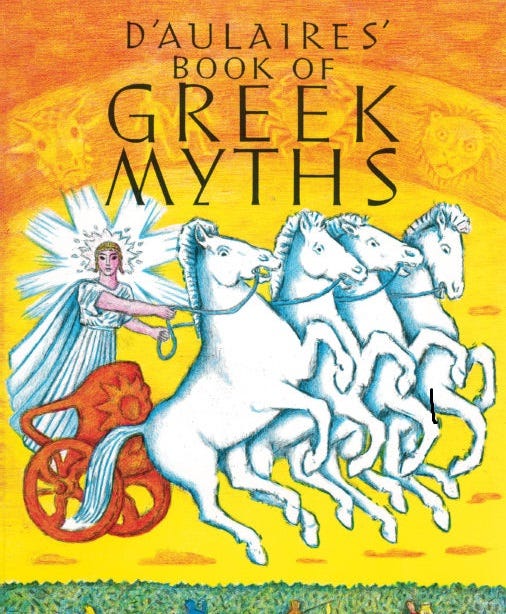

LAURA LORSON writes: “One of my very favorite books is one I got for Christmas in 1974: D’Aulaires’ Book of Greek Myths.

It was a hardcover. I loved its size and weight and adored the artwork along with the stories. I was an early reader and I was 6 when I received it that Christmas morning. I immediately forgot about any other presents and began my lifelong immersion in Classics, mythologies in general, and that book in particular. I used to think that this being my favorite book was something peculiar to me, until I got older and started asking people “what book from your childhood had the biggest impact on you?” and at least half always piped up with “D’Aulaires’ Book of Greek Myths.”

It turns out that Ingri and Edgar Parin D’Aulaire were a part of the group of artists who shaped the aesthetics of picture books in mid-20th Century America…a group that included Ludwig Bemelmans, Roger Duvoisin, Tibor Gergely and Miska Petersham. When you think of books from the 40s, 50s, 60s, and 70s, their illustrations are likely what leap to mind. The D’Aulaires were terrific writers, too…engaging, designed for children, simplifying without dumbing anything down. I didn’t know any of that when I was a kid, I just knew that my book was beautiful and wonderful and I loved it. I read it over and over again, through elementary school, middle school, high school, even carting it off with me to college and graduate school and beyond. Just seeing its iconic cover makes me feel happy.

In fact, every time I head out in my favorite non-rock band t-shirt (see below), at least one person asks me where I got it. It’s a nice little a-ha! moment, when someone at the grocery store stops to tell you “I loved that book!”, a quick one-on-one connection with a stranger in a world where that can feel rare. That Christmas present almost 50 years ago ended up giving me something in common with thousands of people. What a fine thing to give someone. What a true and enduring gift.

[Laura, rocking one of her favorite Tee-shirts]

EMILY MASON writes:

“When thinking about my favorite childhood books, my mind turns almost immediately to The Boxcar Children series by Gertrude Chandler Warner. The original novel was published in 1929, and became a series in 1949.

What started as a story of four orphaned siblings living in an abandoned boxcar quickly turned into a series about four orphaned siblings solving mysteries.

Yes, this is strange, but their strangeness is part of what makes the books so appealing. When you’re seven-years-old, this orphans in a boxcar/mystery-solving combination is perfectly logical. It’s the adults that have the problem!

While reading up on the series, I learned that Gertrude Chandler Warner read the original“Boxcar”novel out loud to her classroom of kids (she taught first grade), and reworked sections based on their reactions. Frankly, it shows.

While adults may not get as much out of reading these books, The Boxcar Children holds up because it was and is a series for children. It had everything my friends and I were obsessed with in first grade:

Orphans

Mysteries

Kids with dogs!

Really, I was powerless to resist them.

The siblings also traveled sometimes; there was even a book set in Washington DC, where I grew up. But unlike me and my elementary school friends who were obsessed with these stories, the Boxcar children did not grow up. (The characters, who have not aged, continue working their mysteries — almost a century after their debut.)”

Dear Readers: Thank you for devoting at least part of your day to reading our work.

I hope these origin stories will inspire you to share your own — in the comments section below.

Merry Christmas, and to all …

A good book!

Love,

Amy

Thanks for including me, Amy!

I love this every year! Books are such wonderful things. Also, I’m a huge Sherman Alexie fan so I’m so grateful he was a part of this post! ❤️